Abstract

Chronic pain and opioid use disorder (OUD) represent two intertwined global health crises, posing immense challenges to individuals, healthcare systems, and societies. This comprehensive review meticulously explores the intricate pathophysiology, varied clinical manifestations, and profound socioeconomic impact of chronic pain, delving into its diverse classifications and multifactorial etiologies. It then critically examines the spectrum of contemporary management strategies, encompassing advanced pharmacological agents, sophisticated interventional procedures, and robust non-pharmacological modalities, emphasizing the paradigm shift towards holistic, patient-centered care. A substantial focus is dedicated to elucidating the complex, often bidirectional, relationship between persistent pain and the development or perpetuation of substance use disorders, particularly opioid dependence, including the insidious phenomenon of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. The report underscores the imperative for integrated, multidisciplinary treatment models designed to concurrently address both conditions. Special attention is given to Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement (MORE), an innovative evidence-based intervention, as a particularly promising and efficacious approach for individuals grappling with the dual burden of chronic pain and OUD, detailing its theoretical underpinnings, core components, and empirical support.

Many thanks to our sponsor Maggie who helped us prepare this research report.

1. Introduction

Chronic pain, conventionally defined as pain persisting or recurring for more than three months, or beyond the typical healing period, is a pervasive and debilitating condition affecting an estimated 20-30% of the global adult population, and even higher percentages in specific demographics, reaching up to 50% in some national surveys (Institute of Medicine, 2011; National Institutes of Health, 2022). It transcends acute nociception, evolving into a complex biopsychosocial phenomenon characterized by neuroplastic changes in the central nervous system, often accompanied by significant psychological distress, functional impairment, and diminished quality of life (Institute of Medicine, 2011). The societal burden of chronic pain is staggering, encompassing direct healthcare expenditures, indirect costs due to lost productivity, and intangible costs related to suffering and reduced well-being.

Concurrently, opioid use disorder (OUD), characterized by a problematic pattern of opioid use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, has emerged as a major public health crisis globally (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2022). Fuelled in part by a period of aggressive opioid prescribing for chronic non-cancer pain, OUD is associated with severe morbidity, including overdose deaths, infectious diseases, and substantial psychosocial dysfunction. The co-occurrence of chronic pain and OUD presents an extraordinarily complex clinical conundrum, with individuals often caught in a vicious cycle where pain drives opioid seeking, and opioid use can paradoxically exacerbate pain and entrench addiction. Effective management necessitates nuanced, integrated, and multidisciplinary treatment paradigms that address both conditions synergistically, moving beyond siloed approaches to foster comprehensive recovery and improved functional outcomes.

Many thanks to our sponsor Maggie who helped us prepare this research report.

2. The Multifaceted Nature of Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is not a monolithic entity; rather, it is a heterogeneous condition influenced by a confluence of biological, psychological, and social factors. Its classification and understanding are critical for targeted intervention.

2.1 Types and Causes of Chronic Pain

Historically, chronic pain has been broadly categorized based on its presumed origin. Recent advancements in pain neuroscience have led to more refined classifications, including the addition of ‘nociceplastic’ pain.

2.1.1 Nociceptive Pain

Nociceptive pain arises from actual or threatened damage to non-neural tissue and is due to the activation of nociceptors, specialized sensory receptors that detect harmful stimuli. This type of pain is typically localized, aching, throbbing, or pressure-like. It can be further subdivided:

- Somatic Nociceptive Pain: Originates from the skin, muscles, joints, bones, and connective tissues. Examples include osteoarthritis (OA), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), lower back pain syndromes stemming from disc herniation or facet joint arthropathy, musculoskeletal injuries that fail to heal, and inflammatory conditions like tendonitis or bursitis. The pain is usually well-localized and aggravated by movement or pressure.

- Visceral Nociceptive Pain: Originates from internal organs. It is often diffuse, gnawing, cramping, or squeezing, and may be referred to distant sites on the body surface. Examples include chronic abdominal pain from conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or endometriosis, chronic pelvic pain, and pain associated with certain types of cancer affecting internal organs. Autonomic symptoms such as nausea or sweating may accompany visceral pain.

2.1.2 Neuropathic Pain

Neuropathic pain results from a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory nervous system, either peripheral or central. It is often described as burning, shooting, stabbing, tingling, numbness, or electric-shock like. Characteristically, it may be accompanied by allodynia (pain from normally non-painful stimuli) or hyperalgesia (increased pain from painful stimuli).

- Peripheral Neuropathic Pain: Caused by damage to peripheral nerves. Common etiologies include diabetic neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia (shingles pain), trigeminal neuralgia, radiculopathies (nerve root compression, e.g., sciatica), phantom limb pain following amputation, and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. The underlying mechanisms involve aberrant nerve firing, ectopic discharges, and changes in ion channel expression.

- Central Neuropathic Pain: Arises from damage to the central nervous system (brain or spinal cord). Examples include pain after stroke, spinal cord injury pain, and pain associated with multiple sclerosis. Mechanisms involve central sensitization, disinhibition, and altered descending pain modulation.

2.1.3 Nociceplastic Pain (formerly ‘Central Sensitization Pain’ or ‘Functional Pain’)

This category describes pain that arises from altered nociception despite no clear evidence of actual or threatened tissue damage causing the pain, or disease or lesion of the somatosensory system causing the pain. It represents a dysregulation of pain processing in the central nervous system, leading to heightened pain sensitivity (central sensitization). The pain is often widespread and accompanied by other somatic symptoms.

- Fibromyalgia: A prototypical example, characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and cognitive dysfunction. The pain is believed to result from an amplification of pain signals by the central nervous system.

- Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis): Often co-occurs with fibromyalgia and involves similar central sensitization mechanisms.

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): Characterized by chronic abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits, often linked to visceral hypersensitivity.

- Temporomandibular Joint Disorder (TMJD): Chronic facial pain often attributed to altered central pain processing.

- Other conditions: Some forms of chronic lower back pain, chronic headaches (e.g., tension-type headaches, migraines that have become chronic), and interstitial cystitis can have nociceplastic components.

2.1.4 Mixed Pain and Idiopathic Pain

Many chronic pain conditions exhibit characteristics of more than one pain type, such as chronic lower back pain which can have nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociceplastic components. Furthermore, some pain conditions remain ‘idiopathic’, meaning no specific cause can be identified, often pointing towards a predominant psychosocial or central processing dysfunction.

Beyond these classifications, the etiology of chronic pain is multifactorial, involving genetic predispositions (e.g., in migraine, fibromyalgia), psychosocial factors (stress, trauma, adverse childhood experiences, lack of social support), environmental influences, and occupational hazards. The transition from acute to chronic pain is not merely a prolonged acute phase but involves complex neurobiological and psychological shifts.

2.2 Impact on Quality of Life

The enduring presence of chronic pain profoundly impacts nearly every facet of an individual’s life, leading to a cascade of negative consequences that extend far beyond the physical sensation of pain. The Institute of Medicine’s report, ‘Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research’ (2011), highlighted the pervasive and devastating effects.

2.2.1 Functional Limitations and Physical Deconditioning

Chronic pain severely impedes physical function. Individuals experience difficulty with activities of daily living (ADLs) such as dressing, bathing, and eating, as well as instrumental ADLs (IADLs) like cooking, cleaning, and managing finances. Reduced mobility, muscle weakness, and joint stiffness become common. The fear-avoidance model of pain suggests that individuals may avoid movements or activities believed to exacerbate pain, leading to disuse, deconditioning, and further functional decline, thereby perpetuating the pain cycle. Sleep disturbances, including insomnia, fragmented sleep, and restless leg syndrome, are highly prevalent, further eroding energy levels and resilience.

2.2.2 Psychological Distress and Comorbidity

Chronic pain is strongly associated with a high prevalence of psychological comorbidities. Depression affects 30-54% of chronic pain patients, while anxiety disorders are seen in 20-60%. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is also significantly more common among individuals with chronic pain, particularly those with a history of trauma (Institute of Medicine, 2011). These mental health conditions are not merely consequences but can also exacerbate pain perception and interfere with treatment effectiveness. Cognitive factors like pain catastrophizing (an exaggerated negative mental set toward pain) and low self-efficacy (belief in one’s ability to cope with pain) are powerful predictors of pain intensity, disability, and emotional distress. Chronic pain can alter brain structure and function, leading to changes in grey matter volume and connectivity in areas involved in pain processing, emotion regulation, and cognitive control, further intertwining physical and psychological suffering.

2.2.3 Social Isolation and Occupational Impairment

The chronic nature of pain often leads to withdrawal from social activities, hobbies, and family engagements due to pain, fatigue, and associated mood disturbances. This social isolation can further deepen feelings of loneliness, depression, and helplessness. Relationships with family and friends can become strained as pain limits participation in shared activities and may lead to misunderstandings about the invisible nature of the suffering. On an occupational level, chronic pain is a leading cause of long-term disability, absenteeism, and presenteeism (reduced productivity at work). Many individuals lose their jobs, experience reduced work hours, or are forced into early retirement, leading to significant financial strain and loss of self-identity previously tied to their professional roles.

2.2.4 Economic Burden

The economic costs of chronic pain are enormous, often exceeding those of heart disease, cancer, and diabetes combined. The Institute of Medicine (2011) estimated that chronic pain costs the United States up to $635 billion annually in direct medical expenditures (hospitalizations, doctor visits, medications, procedures) and indirect costs due to lost productivity (disability payments, lost wages, reduced tax revenues). This burden extends to healthcare systems through increased utilization of emergency services, inpatient admissions, and long-term care, straining resources and diverting funds from other critical public health initiatives.

Many thanks to our sponsor Maggie who helped us prepare this research report.

3. Management Strategies for Chronic Pain

Effective management of chronic pain necessitates a comprehensive, individualized, and often multidisciplinary approach, acknowledging the complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors. The goal extends beyond mere pain reduction to improving function, enhancing quality of life, and fostering self-management capabilities.

3.1 Pharmacological Treatments

Pharmacological interventions remain a cornerstone of chronic pain management, though their selection is guided by pain type, severity, comorbidity, and potential side effects. A stepped-care approach, starting with less potent agents and escalating as needed, is generally recommended.

3.1.1 Non-Opioid Analgesics

These are often first-line agents due to a more favorable side-effect profile compared to opioids, especially for mild to moderate nociceptive pain.

- Acetaminophen (Paracetamol): Effective for mild to moderate pain. Its mechanism involves central action, possibly inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis within the central nervous system. Long-term use requires careful monitoring for hepatotoxicity, especially at higher doses or in individuals with pre-existing liver conditions.

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Work by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes (COX-1 and COX-2), thus reducing prostaglandin synthesis and inflammation. Examples include ibuprofen, naproxen, and celecoxib (a selective COX-2 inhibitor). While effective for inflammatory pain (e.g., osteoarthritis), long-term use carries significant risks including gastrointestinal bleeding and ulcers, renal impairment, and increased cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke), particularly with non-selective NSAIDs or at high doses. COX-2 selective inhibitors may offer some GI safety but still carry cardiovascular risks.

- Topical Analgesics: Applied directly to the skin for localized pain relief, minimizing systemic side effects. Examples include:

- Lidocaine patches/creams: Work by blocking voltage-gated sodium channels in peripheral nerves, reducing nerve excitability and pain signal transmission.

- Capsaicin creams/patches: Derived from chili peppers, these deplete Substance P, a neurotransmitter involved in pain transmission, and desensitize nociceptors. Initial burning sensation is common.

- Topical NSAIDs: Such as diclofenac gel, offer localized anti-inflammatory effects with less systemic absorption compared to oral NSAIDs.

3.1.2 Adjuvant Analgesics

These medications are primarily developed for other conditions but have proven efficacy in specific types of chronic pain, particularly neuropathic and nociceplastic pain, by modulating pain pathways.

- Antidepressants: Effective even in the absence of depression, by modulating descending pain inhibitory pathways involving serotonin and norepinephrine.

- Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs): E.g., amitriptyline, nortriptyline, desipramine. Often used for neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, and chronic tension headaches. They inhibit the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin. Side effects include anticholinergic effects (dry mouth, constipation), sedation, and cardiac conduction abnormalities, limiting their use in older adults or those with cardiac issues.

- Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs): E.g., duloxetine, venlafaxine, milnacipran. Are generally better tolerated than TCAs. Duloxetine is approved for neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, and chronic musculoskeletal pain. They also block the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, enhancing descending pain modulation.

- Anticonvulsants (Gabapentinoids): Primarily used for neuropathic pain.

- Gabapentin and Pregabalin: These agents bind to the alpha-2-delta subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels in the central nervous system, reducing the release of excitatory neurotransmitters involved in pain signaling. They are effective for diabetic neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia, and fibromyalgia. Side effects include sedation, dizziness, and peripheral edema.

- Muscle Relaxants: E.g., cyclobenzaprine, tizanidine, baclofen. Used for acute musculoskeletal spasms and certain types of spasticity. Their utility in chronic pain is generally limited due to side effects and risk of dependence with some agents, though they may offer short-term relief for specific muscular components of pain.

- Corticosteroids: Systemic corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) are potent anti-inflammatory agents useful for short-term management of acute inflammatory flares in conditions like rheumatoid arthritis or acute radiculopathy, but chronic systemic use is limited by severe side effects (e.g., osteoporosis, diabetes, immunosuppression).

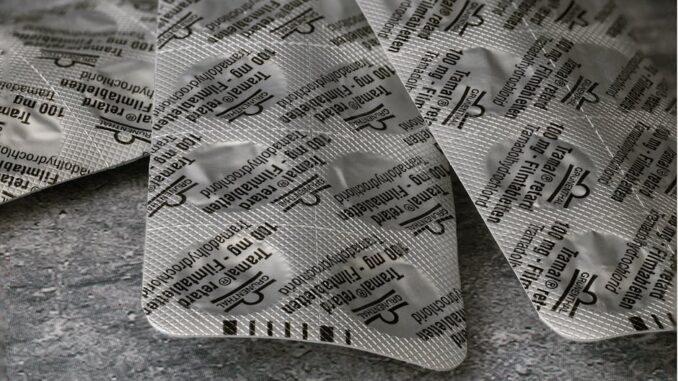

3.1.3 Opioid Analgesics

Opioids bind to opioid receptors in the brain, spinal cord, and gut, modulating pain perception. While crucial for acute severe pain and cancer pain, their role in chronic non-cancer pain has become highly scrutinized due to risks of addiction, overdose, and long-term adverse effects like opioid-induced hyperalgesia (Busse et al., 2017; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017). Current guidelines strongly recommend limiting or avoiding chronic opioid use for non-cancer pain, reserving it for highly selected patients after exhaustion of other options, with rigorous monitoring and a focus on functional improvement rather than solely pain reduction.

3.2 Interventional Treatments

Interventional pain management techniques directly target the anatomical sources or pathways of pain using minimally invasive procedures, often guided by imaging.

- Nerve Blocks: Involve injecting local anesthetics, sometimes with corticosteroids, near nerves or nerve plexuses to block pain signals. Examples include epidural steroid injections for radicular pain, facet joint injections for spinal arthritis, and sympathetic nerve blocks for complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).

- Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA): Uses heat generated by radiofrequency currents to lesion nerves, effectively deactivating them from transmitting pain signals. Commonly used for chronic back and neck pain from facet joints or sacroiliac joints.

- Neuromodulation: Involves implanting devices that deliver electrical impulses to the nervous system to modulate pain signals.

- Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS): Delivers low-voltage electrical current to the spinal cord, replacing pain with a tingling sensation (paresthesia) or no sensation. Effective for neuropathic pain, failed back surgery syndrome, and CRPS.

- Dorsal Root Ganglion (DRG) Stimulation: A newer form of neuromodulation targeting specific DRGs, which are collections of nerve cell bodies involved in transmitting pain signals. Offers more targeted pain relief for focal neuropathic pain conditions.

- Peripheral Nerve Stimulation (PNS): Targets specific peripheral nerves. Useful for localized neuropathic pain.

- Intrathecal Drug Delivery Systems: Involve implanting a pump that delivers medication (e.g., opioids, local anesthetics, baclofen) directly into the cerebrospinal fluid, allowing for much lower doses and fewer systemic side effects compared to oral administration. Reserved for severe, intractable pain.

- Surgical Interventions: While not typically considered primary pain management, surgery may be necessary to correct underlying structural causes of pain (e.g., spinal fusion for instability, joint replacement for severe osteoarthritis, nerve decompression for entrapment neuropathies) when other conservative measures fail.

3.3 Non-Pharmacological Approaches

Non-pharmacological strategies are increasingly recognized as foundational for chronic pain management, emphasizing self-management, functional restoration, and psychological well-being.

3.3.1 Physical Therapy (PT) and Occupational Therapy (OT)

These therapies are crucial for restoring function and improving physical capacity. PT focuses on:

- Therapeutic Exercise: Strengthening weakened muscles, improving flexibility, and increasing cardiovascular fitness (e.g., low-impact aerobics). This combats deconditioning and improves pain tolerance.

- Manual Therapy: Techniques like massage, mobilization, and manipulation to address muscle tightness, joint stiffness, and soft tissue restrictions.

- Modalities: Such as heat, cold, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and ultrasound, used adjunctively for symptom relief.

OT assists patients in adapting to their pain and improving their ability to perform daily tasks through:

- Activity Pacing: Teaching patients to balance activity with rest to prevent exacerbations.

- Ergonomic Assessment: Modifying workspaces or home environments to reduce physical strain.

- Energy Conservation Techniques: Strategies to manage fatigue and preserve energy for essential activities.

3.3.2 Psychological Interventions

Addressing the psychological dimensions of chronic pain is paramount, as thoughts, emotions, and behaviors significantly influence pain perception and disability.

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT): A highly evidence-based therapy that helps patients identify and challenge maladaptive thoughts and beliefs about pain (e.g., ‘I can’t do anything because of my pain’) and replace them with more adaptive ones. It also teaches behavioral strategies like activity pacing, graded exposure (gradually re-engaging in feared activities), and relaxation techniques (e.g., diaphragmatic breathing, progressive muscle relaxation). CBT aims to reduce pain interference, improve coping skills, and enhance self-efficacy.

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): A third-wave behavioral therapy that emphasizes psychological flexibility. Instead of trying to eliminate pain, ACT teaches patients to accept unwelcome thoughts and feelings (including pain) as they are, without judgment, while committing to actions aligned with their personal values. It utilizes mindfulness, defusion (distancing from thoughts), and value clarification to help patients live meaningful lives despite pain.

- Biofeedback: A technique where patients learn to control involuntary bodily functions (e.g., muscle tension, heart rate, skin temperature) through real-time monitoring, often used to reduce muscle tension or mitigate stress responses contributing to pain.

3.3.3 Complementary and Integrative Health (CIH)

A growing body of evidence supports the use of various CIH approaches as adjuncts to conventional care.

- Acupuncture: An ancient Chinese practice involving the insertion of thin needles into specific points on the body. Proposed mechanisms include the release of endogenous opioids, modulation of neurotransmitters, and effects on the central nervous system. It has demonstrated efficacy for various chronic pain conditions, including back pain, osteoarthritis, and headaches.

- Massage Therapy: Manual manipulation of soft tissues can reduce muscle tension, improve circulation, and promote relaxation, offering temporary pain relief and improved well-being.

- Yoga and Tai Chi: Mind-body practices that combine physical postures, breathing exercises, and meditation. They improve flexibility, strength, balance, and body awareness, and have shown benefits for chronic back pain, fibromyalgia, and arthritis by reducing pain, improving function, and decreasing stress.

- Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR): A structured 8-week program that teaches various mindfulness meditation practices, including body scan, sitting meditation, and mindful movement. MBSR enhances present-moment awareness, non-judgmental observation of sensations (including pain), and emotional regulation, leading to reduced pain intensity and improved coping.

- Diet and Nutrition: While not a direct pain treatment, an anti-inflammatory diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins, and low in processed foods and refined sugars, may help reduce systemic inflammation contributing to certain pain conditions.

3.3.4 Self-Management Programs

These programs empower individuals with chronic pain to actively participate in their own care. They typically involve education about pain mechanisms, development of coping strategies, goal setting, pain pacing, communication skills, and relapse prevention techniques. The Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) is a widely recognized example (Barlow et al., 2002).

Many thanks to our sponsor Maggie who helped us prepare this research report.

4. Opioid Use Disorder and Chronic Pain

The nexus between chronic pain and opioid use disorder is a public health challenge of immense proportions. Understanding this complex relationship is paramount for developing effective and ethical treatment strategies.

4.1 The Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of OUD

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronic, relapsing brain disease characterized by compulsive opioid seeking and use despite harmful consequences (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2022). Its diagnosis is based on criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), which include impaired control over opioid use, social impairment due to opioid use, risky use, and pharmacological criteria such as tolerance and withdrawal.

4.1.1 Risk Factors for OUD in Chronic Pain Patients

While prescription opioids can be effective for acute pain, their long-term use for chronic non-cancer pain significantly increases the risk of OUD. Key risk factors among chronic pain patients include:

- History of Substance Use Disorder: Prior or current problematic use of alcohol, illicit drugs, or other prescription medications.

- Mental Health Comorbidities: High rates of co-occurring depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD, and other psychiatric conditions are strong predictors of OUD development.

- Higher Opioid Doses and Long-Term Use: Escalating doses and prolonged duration of opioid therapy significantly increase OUD risk. The CDC guidelines recommend extreme caution for doses exceeding 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day (Dowland et al., 2016, as cited in National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017).

- Social Determinants of Health: Poverty, unemployment, lack of social support, and history of abuse or trauma can exacerbate vulnerability.

- Genetic Predisposition: Genetic factors can influence an individual’s susceptibility to both chronic pain and addiction.

4.1.2 Neurobiology of Addiction

OUD involves profound neurobiological changes in the brain’s reward system. Opioids, like other addictive substances, hijack the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, which originates in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and projects to the nucleus accumbens (NAc), prefrontal cortex (PFC), and amygdala. Acute opioid use leads to a surge in dopamine release in the NAc, producing intense feelings of pleasure and reinforcing the drug-taking behavior.

Chronic opioid exposure, however, leads to neuroadaptations:

- Tolerance: The need for progressively higher doses of opioids to achieve the same effect, due to down-regulation of opioid receptors and changes in cellular signaling pathways.

- Physical Dependence: The development of withdrawal symptoms upon abrupt cessation or reduction of opioid use, reflecting the body’s physiological adaptation to the continuous presence of the drug.

- Sensitization of Reward Pathways: Paradoxically, while the initial euphoric effects may diminish, the brain’s circuitry responsible for craving and motivation becomes sensitized, leading to compulsive drug-seeking behavior. The prefrontal cortex, involved in executive function and decision-making, also undergoes changes, impairing judgment and impulse control.

- Stress Systems: Activation of brain stress systems (e.g., hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, norepinephrine systems) during withdrawal contributes to negative emotional states, reinforcing drug use to alleviate distress.

4.2 The Interplay Between Chronic Pain and OUD

The relationship between chronic pain and OUD is bidirectional and mutually exacerbating, creating a complex cycle that is challenging to break.

4.2.1 Self-Medication Hypothesis

Many individuals with chronic pain initially receive opioids as a legitimate medical treatment. However, some may escalate their use or divert their medication to cope with unmanaged pain, emotional distress, or psychological comorbidities like depression and anxiety. The ‘self-medication hypothesis’ posits that individuals use substances to alleviate negative affective states or psychiatric symptoms. For chronic pain patients, this can manifest as using opioids not just for pain relief, but also for sedation, mood elevation, or to escape from overwhelming emotions related to their chronic condition. This can quickly transition from appropriate use to problematic use and eventually OUD.

4.2.2 Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH)

Perhaps one of the most insidious aspects of long-term opioid use in chronic pain is the phenomenon of opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH). OIH is a state of increased pain sensitivity caused by exposure to opioids. Paradoxically, as individuals take more opioids, their pain can worsen, become more widespread, or change in character, often described as a burning or diffuse pain. This leads patients to request higher opioid doses, perpetuating a dangerous cycle.

Mechanisms underlying OIH are complex and include:

- Activation of Pro-Nociceptive Pathways: Chronic opioid use can activate descending facilitatory pathways that enhance pain signaling.

- Glial Cell Activation: Opioids can activate glial cells (e.g., microglia, astrocytes) in the central nervous system, leading to the release of inflammatory cytokines and neurotoxic substances that heighten neuronal excitability.

- NMDA Receptor Sensitization: Opioids can indirectly activate and sensitize N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, which are involved in central sensitization and pain amplification.

- Dysregulation of Endogenous Opioid Systems: Chronic exogenous opioid exposure can disrupt the body’s natural opioid system, reducing the effectiveness of endogenous pain relief mechanisms.

OIH can be clinically challenging to differentiate from tolerance or withdrawal, as all three can result in increased pain. However, OIH manifests as new or worsening pain despite stable or increasing opioid doses, whereas tolerance typically means a diminished analgesic effect, and withdrawal involves a constellation of symptoms including pain upon dose reduction or cessation.

4.2.3 Co-occurring Mental Health Disorders

The high rates of co-occurring mental health disorders (depression, anxiety, PTSD) among chronic pain patients significantly complicate the picture. These conditions independently increase the risk of OUD and make both pain and addiction more difficult to treat. For instance, anxiety can amplify pain perception, and pain can exacerbate anxiety, creating a feedback loop. Individuals struggling with both pain and mental illness may be particularly vulnerable to misusing opioids in an attempt to self-medicate their emotional distress, rather than solely their physical pain.

4.2.4 Impact on Treatment Outcomes

The co-occurrence of chronic pain and OUD negatively impacts treatment outcomes for both conditions. Pain management strategies may be less effective in the presence of active OUD, and OUD treatment can be complicated by the presence of severe, ongoing pain. Patients may drop out of addiction treatment if their pain is inadequately managed, or they may struggle to adhere to pain management plans due to craving and drug-seeking behaviors. This necessitates a truly integrated and coordinated approach.

4.3 Risks of Opioid Use in Chronic Pain Management

Beyond OUD, long-term opioid use carries numerous significant risks:

- Addiction: As previously discussed, this is the primary concern, transforming physical dependence into a compulsive behavioral disorder.

- Overdose: Opioids cause dose-dependent respiratory depression, the primary cause of fatal and non-fatal overdoses. Risk factors include higher doses, co-ingestion of other central nervous system depressants (e.g., benzodiazepines, alcohol), and a history of previous overdose. Naloxone is a life-saving opioid antagonist used to reverse overdose.

- Tolerance and Dependence: While distinct from addiction, these physiological adaptations increase the challenge of opioid tapering and cessation, requiring careful medical supervision to manage withdrawal symptoms.

- Other Adverse Effects: Chronic opioid use can lead to a range of other debilitating side effects:

- Opioid-Induced Constipation (OIC): A highly prevalent and often severe side effect due to opioid effects on gut motility.

- Nausea and Vomiting: Especially common at treatment initiation or dose escalation.

- Hormonal Imbalances: Opioid-induced hypogonadism (low testosterone in men, menstrual irregularities/amenorrhea in women) is common, leading to symptoms like fatigue, low libido, and osteoporosis.

- Cognitive Impairment: Drowsiness, impaired concentration, and reduced psychomotor speed can affect daily functioning, driving, and safety.

- Sleep-Disordered Breathing: Opioids can worsen or induce central sleep apnea.

- Immunosuppression: Chronic opioid use may suppress the immune system, increasing susceptibility to infections.

- Cardiovascular Risks: Less direct, but some studies suggest an association with cardiac arrhythmias or other cardiovascular events.

Many thanks to our sponsor Maggie who helped us prepare this research report.

5. Integrated Treatment Approaches

Addressing the complex, co-occurring conditions of chronic pain and opioid use disorder demands a shift from traditional, siloed approaches to integrated, holistic, and patient-centered care. This multidisciplinary framework is essential for optimizing outcomes for both conditions.

5.1 Principles of Integrated Care

Integrated care models for chronic pain and OUD are founded on several core principles:

- Patient-Centeredness: Tailoring treatment plans to the individual’s unique needs, preferences, values, and goals, fostering shared decision-making.

- Holistic Approach: Addressing the biological, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions of pain and addiction.

- Coordination and Communication: Ensuring seamless collaboration and information exchange among all members of the treatment team.

- Stepped Care Model: Progressing from less intensive to more intensive interventions as needed, based on patient response and risk stratification.

- Longitudinal Care: Recognizing chronic pain and OUD as chronic conditions requiring ongoing management and support, rather than episodic treatment.

5.2 Multidisciplinary Care Team

An effective integrated treatment program typically involves a diverse team of healthcare professionals who work collaboratively to provide comprehensive care:

- Primary Care Providers (PCPs): Often the first point of contact, PCPs play a crucial role in initial screening, diagnosis, opioid prescribing oversight, and coordinating referrals to specialists. They manage overall health and chronic medical conditions.

- Addiction Specialists: Physicians (e.g., addiction medicine specialists, psychiatrists) and licensed addiction counselors trained in diagnosing and treating substance use disorders. They manage medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for OUD and provide behavioral therapies for addiction.

- Pain Clinicians: Physicians specializing in pain management (e.g., anesthesiologists, neurologists, physical medicine and rehabilitation specialists) who offer expertise in advanced diagnostic techniques, interventional procedures, and non-opioid pharmacological strategies.

- Behavioral Health Professionals: Psychologists, psychiatrists, and licensed clinical social workers who provide psychological interventions (e.g., CBT, ACT, MBSR), address mental health comorbidities (depression, anxiety, PTSD), and support coping skills and emotional regulation.

- Physical and Occupational Therapists (PT/OT): Essential for restoring physical function, improving mobility, teaching safe movement patterns, and adapting daily activities. They combat deconditioning and promote active self-management.

- Pharmacists: Provide expertise on medication interactions, adverse effects, and appropriate dosing, playing a vital role in medication reconciliation and patient education.

- Social Workers/Case Managers: Assist patients with navigating the healthcare system, accessing community resources, addressing socioeconomic barriers, and coordinating care.

Effective communication among these team members is paramount to ensure consistency of care, prevent conflicting advice, and facilitate shared understanding of the patient’s complex needs.

5.3 Pharmacological Treatments for OUD in Pain Patients

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is the gold standard for OUD and has demonstrated superior outcomes compared to behavioral therapies alone. For patients with co-occurring chronic pain, MAT can also help stabilize pain and improve functional outcomes.

- Buprenorphine/Naloxone (Suboxone, Subutex): Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist, meaning it produces weaker opioid effects than full agonists like methadone or heroin, with a ceiling effect that reduces the risk of respiratory depression and overdose. It alleviates withdrawal symptoms and cravings. Naloxone is added to deter intravenous misuse. Buprenorphine can also provide analgesic effects, making it particularly advantageous for patients with chronic pain. It can be prescribed in outpatient settings by waivered physicians, increasing accessibility.

- Methadone: A full opioid agonist, methadone has been used for decades in Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs) to treat OUD. It reduces cravings and withdrawal symptoms, providing a stable opioid level that prevents euphoric highs. Methadone also has analgesic properties and can be used to manage chronic pain concurrently with OUD. However, its dispensing is highly regulated, requiring daily visits to specialized clinics.

- Naltrexone (Vivitrol, ReVia): An opioid antagonist that completely blocks opioid receptors, preventing both the euphoric and analgesic effects of opioids. It is available in oral and long-acting injectable (Vivitrol) forms. Naltrexone is useful for relapse prevention after detoxification but requires complete opioid abstinence before initiation to avoid precipitated withdrawal. Its use in chronic pain patients can be challenging, as it precludes the use of opioid analgesics if needed.

The choice of MAT depends on various factors, including patient preference, severity of OUD, pain characteristics, and access to different treatment modalities. The integration of MAT with pain management strategies is crucial, often requiring careful dose titration and communication between providers.

5.4 Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement (MORE)

Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement (MORE) is an innovative, manualized group therapy program developed by Dr. Eric Garland, specifically designed to concurrently target chronic pain, opioid misuse, and emotional distress (Garland et al., 2014). It synthesizes principles from three distinct therapeutic traditions:

- Mindfulness Training: Cultivating present-moment awareness and non-judgmental acceptance.

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Identifying and modifying maladaptive thoughts and behaviors.

- Positive Psychology: Fostering positive emotions, strengths, and well-being.

5.4.1 Core Components of MORE

MORE typically consists of eight weekly 2-hour group sessions, structured to progressively build skills in three core areas:

- Mindfulness: Participants learn to observe their thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations (including pain and cravings) with non-judgmental awareness, detaching from their automatic reactions. Practices include breath awareness, body scan meditation, mindful movement, and mindful observation of sensory experiences. The goal is to shift attentional bias away from pain and craving and towards a broader, more flexible awareness.

- Reappraisal: Derived from cognitive restructuring in CBT, this component teaches participants to reframe their relationship with pain and craving. Instead of viewing pain as an unbearable threat, they learn to separate the raw sensation from the suffering. For cravings, participants learn to observe urges without immediately acting on them, recognizing them as transient mental events rather than commands. This involves exercises like cognitive defusion and compassionate self-inquiry.

- Savoring: A key positive psychology intervention, savoring involves intentionally noticing, appreciating, and prolonging positive emotional experiences in daily life. This helps to counteract the ‘reward deficiency’ often seen in chronic pain and addiction, where natural rewards become less salient, driving individuals to seek intense, artificial rewards (like opioids). Savoring practices include mindful attention to pleasant sensory experiences (e.g., taste, smell, sight) and reflection on positive memories or anticipation of future positive events. By enhancing the sensitivity of the brain’s natural reward systems, savoring aims to reduce the hedonic drive for opioids.

5.4.2 Theoretical Underpinnings

MORE’s efficacy is rooted in several theoretical mechanisms:

- Affective Dysregulation: Chronic pain and OUD are often characterized by heightened negative affect (anxiety, depression, irritability) and diminished positive affect. MORE aims to reduce negative affect through mindfulness and reappraisal, and enhance positive affect through savoring.

- Attentional Biases: Individuals with chronic pain often exhibit attentional bias towards pain-related stimuli, and those with OUD towards drug-related cues. Mindfulness training in MORE helps redirect attention and improve attentional control, reducing automatic reactivity to pain and cravings.

- Reward Deficiency Syndrome: Chronic opioid use can blunt the brain’s natural reward pathways. Savoring aims to restore sensitivity to natural rewards, thereby reducing the drive for exogenous opioids to feel pleasure.

- Neurobiological Changes: Research suggests MORE may modulate neural pathways involved in pain processing (e.g., insula, anterior cingulate cortex), reward processing (e.g., ventral striatum, prefrontal cortex), and emotional regulation (e.g., amygdala, prefrontal cortex connectivity), potentially reversing some of the maladaptive neuroadaptations associated with chronic pain and OUD.

5.4.3 Evidence Base

Numerous studies, including randomized controlled trials conducted by Garland and colleagues, have demonstrated the efficacy of MORE (Garland et al., 2014). Key findings indicate that MORE significantly reduces:

- Opioid Misuse: Reductions in prescription opioid misuse, illicit opioid use, and opioid cravings.

- Chronic Pain: Decreases in pain intensity, pain-related functional interference, and physical and psychological pain symptoms.

- Emotional Distress: Significant reductions in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress.

Furthermore, MORE has been shown to increase positive emotions, enhance natural reward processing, improve self-regulation, and promote changes in brain activity associated with improved pain modulation and reduced craving. Its transdiagnostic approach, simultaneously targeting core mechanisms underlying both conditions, makes it a powerful intervention for this dually diagnosed population. MORE has been applied in various settings, including outpatient clinics and primary care, demonstrating its potential for broader dissemination.

Many thanks to our sponsor Maggie who helped us prepare this research report.

6. Challenges and Future Directions

Despite advancements in understanding and treating chronic pain and OUD, significant challenges persist, highlighting areas for future research, policy, and clinical innovation.

6.1 Barriers to Effective Management

- Stigma: Both chronic pain and OUD are heavily stigmatized conditions. Patients with OUD often face moralistic judgments from healthcare providers, family, and society, hindering help-seeking behavior and treatment adherence. Individuals with chronic pain may be dismissed as ‘drug-seeking’ or have their pain invalidated, leading to mistrust in the healthcare system and self-stigma. This societal and institutional stigma creates formidable barriers to accessing integrated, compassionate care.

- Healthcare System Limitations: The current healthcare system is often fragmented, with pain management and addiction treatment operating in silos. There is a severe shortage of pain specialists and addiction medicine professionals, particularly in rural areas, leading to limited access to specialized services. Insurance coverage for non-pharmacological therapies (e.g., physical therapy, psychological interventions, acupuncture) and comprehensive MAT often remains inadequate, forcing patients to rely on less effective or higher-risk interventions. Furthermore, a lack of integrated training for healthcare providers contributes to a deficit in comprehensive skills to manage both conditions concurrently.

- Regulatory Constraints and Policy Issues: Well-intentioned policies aimed at curbing the opioid crisis, such as stringent prescribing guidelines (e.g., CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, 2016) and Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs), have had mixed results. While reducing opioid prescriptions, they have also, in some instances, led to inappropriate opioid tapering or abrupt discontinuation for stable patients, potentially forcing individuals to seek illicit sources, exacerbating withdrawal symptoms, and worsening unmanaged pain (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017). Balancing pain relief with addiction prevention remains a delicate policy challenge.

- Patient-Related Factors: Factors such as health literacy, socioeconomic status, lack of social support, and varying adherence to treatment plans can pose significant barriers to effective management. Complex comorbidities and polypharmacy also complicate care.

6.2 Research Gaps and Opportunities

Addressing the existing knowledge gaps is crucial for advancing the field and improving patient outcomes:

- Long-Term Efficacy and Sustainability: While interventions like MORE show promise, more studies are needed to assess their sustained impact over several years. Research should focus on relapse prevention for OUD and long-term functional improvements for chronic pain after treatment completion. Understanding factors that predict long-term success or relapse is critical.

- Mechanisms of Action: Deeper neuroimaging, genetic, and physiological studies are needed to precisely elucidate how integrated interventions, including MAT and behavioral therapies like MORE, exert their effects on pain and addiction pathways. This could lead to more targeted and potent interventions.

- Personalized Medicine: Developing personalized treatment plans based on individual patient profiles (e.g., genetic predispositions, specific pain phenotypes, psychosocial factors, neurobiological markers) is a key frontier. Identifying biomarkers for OUD risk or optimal response to specific pain treatments could revolutionize care.

- Prevention Strategies: More research is needed on preventing the transition from acute to chronic pain and identifying individuals at highest risk of developing OUD after initial opioid exposure. This includes exploring non-pharmacological approaches for acute pain and early psychosocial interventions.

- Digital Health Interventions: Investigating the efficacy and scalability of telehealth, mobile applications, and remote monitoring systems for delivering integrated pain and OUD care. These technologies could significantly improve access to care, especially for underserved populations.

- Cost-Effectiveness Analyses: Rigorous economic evaluations of integrated care models are needed to inform healthcare policy and resource allocation, demonstrating the long-term cost savings and improved quality of life associated with these comprehensive approaches.

- Health Equity and Disparities: Research is needed to understand and address disparities in access to and outcomes of integrated care for various racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic groups.

Many thanks to our sponsor Maggie who helped us prepare this research report.

7. Conclusion

The co-occurrence of chronic pain and opioid use disorder represents a profound and complex public health challenge, imposing immense suffering on individuals and significant strain on healthcare systems. The intricate interplay between these two conditions, including the insidious phenomenon of opioid-induced hyperalgesia, necessitates a radical departure from fragmented care models.

Integrated, multidisciplinary approaches, which blend advanced pharmacological management (including MAT for OUD), sophisticated interventional techniques, and robust non-pharmacological therapies, are imperative. Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement (MORE) stands out as a particularly promising, evidence-based intervention capable of concurrently addressing the biological, psychological, and social dimensions of both chronic pain and opioid dependence. By cultivating mindfulness, promoting cognitive reappraisal, and enhancing the capacity for savoring natural rewards, MORE offers a pathway to reduce suffering, mitigate opioid misuse, and foster greater well-being and functional capacity.

Overcoming the pervasive stigma, systemic healthcare fragmentation, and policy impediments will require sustained collaborative efforts from researchers, clinicians, policymakers, and communities. Continued investment in rigorous research, particularly focused on long-term outcomes, underlying mechanisms, and personalized medicine, is essential. Only through such comprehensive and compassionate strategies can we hope to alleviate the dual burden of chronic pain and opioid use disorder, improving the quality of life for millions affected worldwide.

Many thanks to our sponsor Maggie who helped us prepare this research report.

References

- Barlow, J. H., Wright, C. C., Sheasby, J. E., Turner, A. P., & Hainsworth, J. M. (2002). Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: A review. Patient Education and Counseling, 48(2), 177-187.

- Busse, J. W., Craigie, S., Juurlink, D., & et al. (2017). Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 189(18), E659-E666.

- Dowland, R. (2016). CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain—United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65(1), 1–49. (Cited in National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017).

- Garland, E. L., et al. (2014). Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement for chronic pain and prescription opioid misuse: Results from an early-stage randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(3), 448-459.

- Institute of Medicine. (2011). Relieving pain in America: A blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. National Academies Press.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). Pain management and the opioid epidemic: Balancing societal and individual benefits and risks of prescription opioid use. National Academies Press.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2022). Opioid use disorder. Retrieved from https://www.nida.nih.gov/health-topics/opioid-use-disorder

- National Institutes of Health. (2022). Chronic pain management. Retrieved from https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/patient-caregiver-education/chronic-pain-management

Be the first to comment